|

| Photos from my album, taken (pre-digital!) in Pompeii, February 1986 |

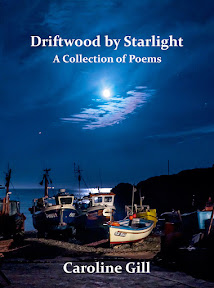

Driftwood by Starlight, my first full poetry collection, was launched online

on Tuesday 3 August. The book was published in June 2021 by Peter

Thabit Jones of The Seventh Quarry Press. It can be purchased for £6.99/$10 from the

publisher's online shop here.

Maria Lloyd, who holds a Masters degree on The City of Rome from the University of Reading,

read the collection and decided to set me some questions about it. I am attempting to provide answers (without giving too much away ...).

Thank you, Maria.

The first post in this mini-series on the blog (click here) concerned my poem 'Monte Testaccio, Mound of Potsherds' on p.35 of the collection.

This second post concerns the poem, 'Wildfire', on p.31. Page numbers in this post refer to Driftwood by Starlight. Let's turn to Maria's questions.

From Maria Lloyd: p.31 'Wildfire'

[Q1] Is this poem based on a specific individual part, or parts of Pompeii that fascinate you and have been combined?

[Q2] Is your repetitive use of 'I wonder who will live and who has died' something that interests you?

[Q3] What is your process in writing poetry? You appear to write many different types of poems. How did you land on the format of each poem?

Once again, here is a little background information before I attempt to offer specific answers. David (Gill), my archaeologist husband, was a Rome Scholar at the British School at Rome

in the mid-1980s. We had recently married and were to spend that year

living in the School, where I washed bones and sherds of pottery in my

spare time. The railways offered what was known as a Biglietto Chilometrico, a pass for 1000 kilometres. We left Rome by train on a snowy morning in February 1986, and arrived in Naples that afternoon. Vesuvius was coated in snow and we were bitterly cold. However, we made the most of our few days in the area, visiting Pompeii, Herculaneum and the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

|

Photo: © Caroline Gill 1986

|

We moved south to Reggio before crossing the Straits of Messina (in the train, on the ferry). We landed in Sicily only to find Etna bathed in warm sunshine. We cast off our winter coats and feasted on gifts of juicy oranges. Perhaps I should backtrack at this point. I spent my junior school years in Kent, not very far from Lullingstone Roman villa, which we visited on a school trip. As a dog-lover, I was fascinated by the Roman paw-prints I saw in bits of tile (and if my previous post alluded to cats, this one will give a nod to the dogs of the Roman world).

|

Pawprints in tile, Lullingstone Roman Villa. Photo: © Caroline Gill

|

Almost ten years later I was able to visit the Pompeii AD79 exhibition at the Royal Academy in London, this time on a secondary school trip. I had not studied any Latin at that point, but I knew about the 'CAVE CANEM'/'Beware of the dog' mosaics, such as the one (with these words) at the entrance to the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii shown below, or the guard dog mosaic (without words) from the House of Orpheus.

|

'CAVE CANEM' mosaic, Pompeii. Photo: © David Gill

|

I went on to study aspects of Pompeii and Herculaneum at university, but it was not until our year (1985-6) in Rome that I was able to see these sites for myself.

Let's turn to the first question.

[Q1] Is this poem based on a specific individual part, or on parts of Pompeii that fascinate you and have been combined?

My 'Roman dog encounters' mentioned above comprise one of several strands that unfurled as I studied (and went on to teach) aspects of classical civilisation, bringing the ancient world to life in my mind's eye. I mention 'life' and yet, of course, when it comes to the devastation caused by the volcanic eruption, we are talking 'death', a fact reflected in the title of the 2013 British Museum exhibition, Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum. 'Wildfire' was not especially based around memories of particular areas or aspects of the archaeological sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum; although, almost inevitably, some features* struck me, or pulled at a proverbial heart-string, more than others. Who would not be affected by the small details (a loaf of bread, for instance, left to smoulder in an oven in Herculaneum) that make the tragedy seem real to those of us who were not there as eye witnesses?

|

| David (Gill) in Herculaneum. Photo: © Caroline Gill |

I have visited Eyam in Derbyshire where plague victims cut themselves off from surrounding villages in order to contain the disease. I have explored the remains of Scottish villages that were abandoned during the Clearances (my poem, 'The Ceilidh House' on p.16 alludes to this). Stones, graves and broken walls can tell a powerful tale, and sometimes these features are all we have to go on. But Pompeii and Herculaneum are different. We are, for example, confronted with the reality of normal aspects of life, including shopping (the Market of Macellum, a fast-food counter ...), art in the form of wall paintings and mosaics, garden features and so much more. It is as if the inhabitants have just gone out for a short while, leaving their stone guard dogs at the ready. And yet it is not at all like that. I find I only have only to stare at the plaster casts made from the remains of the people (see here; and also top right on this blog page for a photo of a figure, head in hands) and their animals (dog, boar or pig, and horse) to begin to sense something of the horror. [Q2] Is your repetitive use of 'I wonder who will live and who has died' something that interests you?

[Q3] What

is your process in writing poetry? You appear to write many different

types of poems. How did you land on the format of each poem?

I am taking these two questions together, and will attempt to answer [Q3], at least in part, in relation to [Q2].

One of the exciting aspects of my poetry journey to date has been exploring the different ways in which 'form' and 'craft' can shape a poem, whether by 'form' I mean something named and specific like the Sestina, and my collection includes one of these ('The Figure at the Phoenix Mine', p.22); or something less precise, perhaps like an unrhymed couplet.

The craft of poetry can be applied in numerous ways, some more tangible (the acrostic in an acrostic poem perhaps, like 'Et in terra pax', p.14), and some more subtle (for example, the deployment of sound-symbolism or contronyms). I was delighted back in 2012 to have three sample 'form poems' (a folding-mirror, a clang and a bref double with echo) included in The Book of Forms including Odd and Invented Forms by Lewis Putnam Turco (UPNE 2012).

Let's turn more specifically to 'Wildfire'. This poem was written during the pandemic; it was not intended to be a 'happy' poem. Poets use the currency of metaphor and sustained metaphor. How much of my poem was actually about the eruption of Vesuvius in AD79? This is a question I continue to ask myself.

What I knew from the outset was that I wanted the reinforcement that repetition would afford. 'Wildfire' is a villanelle (think: 'Do not go gentle into that good night' by Dylan Thomas). The form, allowing for only two rhyme sounds throughout, and the 'pared-back' nature of my theme seemed complementary.

Maria, you highlight my line, 'I wonder who will live and who has died'. Images of those 103 heart-wrenching plaster casts (the child, the man crawling along the ground ...) were rarely far away, but I was also trying to understand what was behind the words written to Tacitus by Pliny the Younger, whose account of the eruption was discovered, or recovered, in the 16th century. Hence the epigraph at the top of my poem. I tried to absorb the text of the letter in translation and attempted to imagine what it might have been like not only for the Younger Pliny, but also for other survivors such as Cornelius Fuscus. Some of those who escaped asphyxiation from the pyroclastic flow at Herculaneum probably left by ship almost as soon as they became aware of the danger. At the time of writing (my records state I began to draft 'Wildfire' on 20 April 2020), I had been in lockdown for some weeks. My outlook was changing, and perhaps that was partly why the subject for this villanelle came to me at that particular moment of flux. People we knew were beginning to catch Covid. There was fear in the air and the virus seemed close at hand.

So much of our knowledge concerning Pompeii and Herculaneum has arisen, phoenix-fashion, from the ashes of civilisation. Thank you, Maria, for your questions; I am left wondering what the current pandemic will teach future generations about the society in which we find ourselves.

* * *

* A few favourites ...

- the spacious House of the Faun, with its mosaic of a Nilotic scene, displaying a crocodile, a hippo, a snake and various ducks. The mosaic is housed in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

- the fresco of Terentius Neo, a baker, and his wife, who holds a writing stylus to her lips and a wax writing tablet in her right hand. I would love to know what she had written or was about to write ...

- Fresco of garden scenes from the the north wall of the House of the Golden Bracelet. I am reminded of William Morris and his 'Strawberry Thief' design ...

- a street with raised stepping stones to allow pedestrians to cross in safety, while allowing access for carts (see my photo below).

|

| February 1986. Photo: © Caroline Gill |

Herculaneum:- the artistic depictions of octopus and dolphins at one end of the black and white mosaic of the Triton (who bears what seems to be an oar) from the women's section of the Central Baths on Cardo IV.

- the Villa of Papyri, with its bronze piglet. I gather this villa was owned by Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, the father in law of Julius Caesar.

- the streets, which seem so real. Some of the adjacent buildings have a second storey.

|

| Photo: © Caroline Gill |

1 comment:

A very interesting read! It makes sense that this poem is partially tied to feelings of concern and threat raised by COVID-19. I enjoyed reading about the highlights at the end. Thank you for sharing.

Post a Comment