|

| Reconstruction (Piet de Jong) of floor motifs, Throne Room, Nestor's Palace, Pylos |

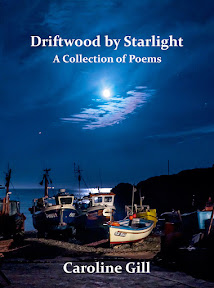

Driftwood by Starlight, my first full poetry collection, was launched online on Tuesday 3 August. The book was published in June 2021 by Peter Thabit Jones of The Seventh Quarry Press. It can be purchased for £6.99/$10 from the publisher's online shop here.

Maria Lloyd, who holds a Masters degree on The City of Rome from the University of Reading, read the collection and decided to set me some questions. I am attempting to provide a few answers in this mini-series (without giving too much away ...). Thank you, Maria.

Post One (click here) concerned my poem 'Monte Testaccio, Mound of Potsherds' on p.35 of Driftwood by Starlight.

Post Two (click here) has as its focus the poem, 'Wildfire', on p.31.

This is Post Three, and we stay with an archaeological theme as we switch our focus from the Roman World to Ancient Greece.

Let's turn to Maria's question. It relates, of course, to all the poems in the collection; but for the purposes of this post I shall apply it to 'The Ocean's Tears' on p.24 and 'Ice-Blue Blood' on p.25:

'You appear to write on a wide range of topics but what were the triggers that made you want to write about these topics in particular?'

Many of us have a sense of adventure lurking somewhere inside us, even if in some cases we turn out to be largely armchair travellers. The classical world has fascinated me for decades so it is not surprising that aspects of ancient Greece and Rome surface in my poems from time to time. The Odyssey is a favourite ancient text.

|

| Homer in hand at Nestor's Palace, 'sandy Pylos', Peloponnese, 2010. Photo: © David Gill |

The two poems I mention above were the result of my engagement with 'Homer', the blind bard. How much of the Iliad and Odyssey can actually be attributed to him is debatable since the tales of Troy are part of the oral tradition in which songs were passed on from singer to singer.

|

| Bust of Homer, Mount Egcumbe |

The two poems I consider in this post exhibit similarities and differences. They are not 'a pair', though it was a deliberate choice to place them opposite one another in the collection. Both concern the tale of Troy to some degree. They each have (in my mind at least) a 20th century UK beach setting.

'The Oceans Tears' is a Tercet Ghazal, a form developed by Robert Bly from the traditional (Arabic) Ghazal of Persian origin. I first encountered Ghazals with a three-lined stanza or 'sher' on The Ghazal Page, a web resource run by Gene Doty, which, sadly, is no longer available.

'Ice-Blue Blood' is also written in three-line stanzas, but (to give words from this poem a new context) there the similarity ends, at least as far as form is concerned.

'The Ocean's Tears' includes a number of items that point to the Homeric world (gold, bronze, arrows and horse). Troy was never far from my thoughts during the drafting of this poem.

|

| Entrance to the 'Troy: Myth and Reality' exhibition, British Museum, 2019-2000 |

Those who have visited King Agamemnon's citadel at Mycenae will be familiar with the cyclopean walls to which I allude in the third verse.

|

| Mycenae, linked to King Agamemnon. Photo: © David Gill |

|

| The Lion Gate entrance to the citadel at Mycenae. Photo: © David Gill |

|

| Mycenaean walls, with jeep for scale. Photo: © David Gill |

'Ice-Blue Blood', on the other hand, begins with an epigraph from William Cowper's translation of Homer about a many-legged creature. I have long been intrigued by artistic renderings of octopus and squid in the Ancient World (see assorted examples on Greek pottery below), and have wondered whether these representations have any symbolic meaning beyond the visual. I believe I read that in one part of the ancient Greek world, the octopus motif could have been applied as a kind of early trademark, but I would need to explore this further.

|

| Octopus fragment found at Phylakopi, Melos (Fitzwilliam Museum) |

|

| Octopus (9), Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY (early 20th century reproduction of stirrup jar, Crete) |

|

| Octopus in the 'Troy' exhibition, British Museum |

|

| Amphora from Tholos tomb II at Routsi, Archaeological Museum of Chora, near Pylos |

The octopus was a popular part of the so-called 'Marine Style' of pottery, which originated on Crete in the late Bronze Age and was embraced by potters on the mainland. Monsters, some more cephalopod-like than others, abound in Greek mythology. They are not all creatures of the sea. The Hydra, which appears in a number of myths and sources such as Hesiod, had several heads. Cerberus, or Kerberos, the hound referred to but not actually mentioned by name in the Iliad, had two, three, or even 'many' heads.

The first open lecture I attended as an undergraduate at Newcastle University in 1979 was given by Dr John Pinsent of Liverpool University on the unusual theme of ancient art and cephalopods. He had authored a paper called The Iconography of Octopuses: a First Typology (BICS 25, 1978) about the development of octopus representations in late Mycenaean vase painting.

More recently I came under the influence of a large blue graffiti octopus known locally as 'Digby'. Digby, designed by John D. Edwards, is part of the Never Ending Mural community arts project in Ipswich and a popular local icon (see here). There may well be a nod to the spirit of Digby in my poem. And, as I hinted earlier, the impact of squid and octopus representations on ancient artifacts should not be overlooked. There is something very fluid, fascinating and changeable about these marine animals. It is worth remembering that while the wine-dark purple colour from the Murex shell (see also here) was prized as a costly dye in Ancient Greece, humans have been writing and drawing with cuttlefish ink, known to us as 'sepia', since times of antiquity.

Speaking of early writing, I began with a photograph relating to Nestor's Palace at Pylos in the western Peloponnese. It seems worthy of note that large quantities of Linear B tablets were found here. Ironically, these clay tablets were baked, and therefore preserved for posterity, in a devastating fire.

|

| Linear B tablet (a cast, I think), Archaeological Museum of Chora |